Since day one of Phyrexia: All Will Be One (ONE), speed of the format was considered an issue. Even though it was based on the Early Access data, unsuitable for drawing such conclusions, the community at large decided that ONE is an extremely fast format and that was it. A thing I learned about Magic internet community is that it takes up what fits their intuition very quickly and with little validation. And equally since day one of ONE, I was pretty skeptical of that sort of sweeping statement.

Over the course of this article I will try to convince you that the answer to the question “Is ONE fast?” is much more complicated and nuanced than “Yes” based on the average length of a game metric. And looking deeper into the game speed can shed more light on the reasons for the speed of this format and increase your understanding on how to counteract it efficiently.

In particular, one thing didn’t fit in the picture from the 17Lands graphic showing the early format speed. The uncharacteristic decoupling of being on the play and format speed. Normally the faster the format, the greater advantage of winning the coin flip at the start of the game. This is fairly consistent across multiple formats:

As you can see the game length and win rate on play correlate very well: the shorter the games, the biggest advantage of being on the play. And that is logical. Being on the play gives you the advantage of having more mana first, deploying your threats earlier. This gives the person on the play advantage in the early game phases (usually until turn 8 or so). But the longer the game lasts, the larger the advantage given to the person on the draw, the extra card they get. At around turn 9 the advantage of starting is minimal, but the advantage of having drawn one card extra is very much real.

This means in formats where games last fewer turns there will be fewer games lasting more than 8 turns, and as a result, being on the play will be advantaged. But even though ONE is a format where games don’t last long, the advantage of being on the play is not following the trend.

This didn’t compute with me. If the format is generically that fast, I expect a large advantage of being on the play. If I don’t see it, there are several hypotheses I can explore. Firstly, maybe the data under-measured the play/draw advantage. Secondly, maybe the format is slower than data suggests. Thirdly, maybe the short duration of the game is linked to something else than the format being distinctly fast. First two hypotheses seem pretty weak to me. If we got the right data in Play/Draw, why do we get biased game duration data? And vice versa. But the third hypothesis seems pretty valid. This made me think, what could cause games last fewer turns but not impact play draw, and then it struck me: deck power disproportions would do exactly that. Some deck would just lose reliably and quickly independent if they are on the play or on the draw, which would make the games shorter in general but without the play/draw advantage, because those decks would just lose independently of who starts.

Time to test it! But first let’s look at the speed of ONE and what speed means in general. In Fig. 2 you can see that the average game duration in the last 20ish formats was between 10.2 and 8.9 turns. ONE is a clear outlier with 8.4 turns. But what does it mean? Average game duration is a single number that describes hundreds of thousand games. Surely there must be a way of representing it in a more telling way.

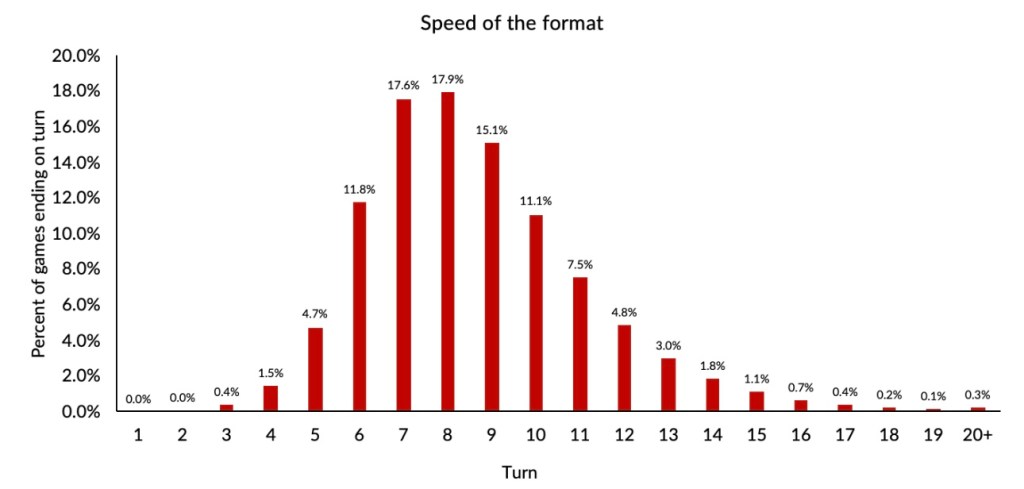

Here we have a histogram of all the ONE draft games by duration. As you can see, large datasets tend to yield neatly looking data following a lovely bell curve, skewed because there is only that fast you can win a game of Magic. How to read this graph? Each number tells us what fraction of all the games in ONE ends on a given turn. So most games end on turn 8 (17.9%) and 7 (17.6%). But that kind of data tells us not much in isolation. How does ONE compare to other formats?

Comparing the same curve in ONE and BRO you can instantly see that ONE is a faster format than BRO. Higher percentage of games are won early in ONE, higher percentage of games are won late in BRO. Easy as that. We can even show it in a more human friendly version – the cumulative graph where we see total fraction of wins by turn X – how many games end by each given turn, to better visualise that difference in speed.

And here you can also see that speed difference. On turn 8, 55% of games in ONE are finished. But in BRO it is only 40% – that is a large difference. We solved the case, time to go home and play some Alchemy, everyone’s favourite format! But wait, that still doesn’t explain that quirky result in terms of play draw advantage. Why a clearly faster format doesn’t show an expected difference in play/draw wins? And here comes a bit of subtlety of data. We are looking at game lengths but only in a very generic way. We could easily stop here, but why not dig a bit deeper?

My hypothesis from earlier was that the speed is impacted not by the generic “fastness” of the format, but by the disproportion in decks ability to be relevant in the format. If that is the case there are two predictions. Firstly, 17Lands.com users are much better in knowing what the format is about than average Arena user. This is not controversial. The 17L users are invested players, they have a track record of posting win rates well above 50% despite competing in a ranked format, that should at least theoretically push the win rate towards 50%. If that is the case, then they should be beneficiaries of a format where game speed is determined by the gap in deck quality. What does it mean? We should see that the games they win are very fast, but the games they lose – not so. Because if the fast losses are linked to not having a deck suitable for the format, the losses of 17L players should not be as fast as their wins. Let us take a look:

The cumulative curves of only wins look very similarly to the one looking at all the games. They do seem to be a bit more separated, suggesting that indeed the games 17L users won were a bit faster than the average of all games, but don’t worry we will look into that later. So how do the lost games look like?

Now that does look very different. The two curves almost overlap and if anything, it looks like BRO was a faster format when comparing those two. More games ended by turn 5-6 in BRO than in ONE. Only after turn 11 you see a very slight advantage of ONE. This means that BRO had more very short games that 17L users lost, but then, it also had more longer games lost. ONE has a less diverse window of losing the game.

More importantly, these two results are very consistent with my earlier hypothesis. The speed of ONE is dictated by the fact that 17L users win much faster than in BRO, not by the fact that the format is generically faster. Let’s look at the raw average number of turns numbers:

And here you can see it best. Lost games, well the average duration of them is almost identical, with BRO being actually a bit faster. But in won games there is a real chasm. ONE games won by 17L users are a whole turn faster than BRO games they won. This is very much consistent with my earlier hypothesis of disproportion of understanding the format as the main driver of the game duration.

But don’t get me wrong. Speed is still important in this format. But in a more subtle way. Looking at the data from BRO you can notice that the games that 17L users won actually took a bit longer than the losses. This is most likely because of the properties of the format. BRO was a good place to play, what I called, a mid-term deck. Decks where you spent early turns setting up the playing field, which prevented you from winning early, and then took over by mana efficiency and board superiority using abundance of small threats. This meant that those decks were slightly slower but very consistent. This also meant that 17L users figured out the power of mechanics like unearth in the mid game, and built the decks accordingly. Building a purely aggressive deck was a less successful strategy, which meant they would apply it less frequently – something we can see in the game duration data.

ONE is a format where early board presence is key. Not really to win, but to survive. Without early drops you will struggle to win games, something that people consuming content will know very well. They build decks designed to survive the early onslaught from the opponents: with cheap removal, combat trick and plenty of early drops. But the side effect of building your decks this way is that when paired against someone who doesn’t, you will have a very good chance of being the beatdown.

And there is another piece of data that points to this direction. The strange discrepancy in ALSA between the colors. It seems that the general population of Arena was forcing toxic aggro decks, leading to them being overdrafted. There are only that many pieces of cheap removal and 2-drops in each color, meaning that venturing into overdrafted colors will lead to decks that have shortages of such cards. And early losses to drafters who pounced on open and aggressively slanted red and white decks not relying on toxic ability.

One thing I hope this article will cause is show how important it is to look a bit deeper into the data before jumping into conclusions. Data will very often present you with one convenient number but that number is composed of thousands of games. Sometimes it is worth looking into what makes them up. One good example is the Game in Hand Win Rate. It is not a complete answer to cards power. it is impacted by the ALSA, it is impacted by the set’s color power, by specificity to some archetype, difficulty of play, even to particular role in some niche sub build or being disproportionally played by a subset of 17Lands users.

But this is a story for another time. Meanwhile, if you want to see my seminar on the topic of speed that also looks at how to build slower decks in this format – why not check my seminar on the topic?